Prostration was

freely practised in private Jewish-Sufi

liturgy and personal devotion and this is clearly indicated in a responsum

of Rabbenu Abraham himself. Elisha Russ-Fishbane

describes and translates it for us as follows:

The questioner was

careful to note that the pietists comported themselves differently when praying

in the main synagogues than when congregating in their private prayer circles.

“When they pray in a mixed group in the

synagogues... they pray together according to the established custom, so as not

to burden the congregation with something that it cannot sustain,” thus making

themselves indistinguishable from other worshipers (except perhaps for their mode

of dress) out of deference to the congregation.

But it is another matter “when they pray alone in their homes or when

they gather for public prayer in houses of study (be-vet midrashim).” On

these occasions, they sit for the “hymns of praise” (pisuqe zimra) and for the

blessings of the recitation of shema‘ in fear and awe, their faces

toward the holy [ark], which is in the direction of the land of Israel and

Jerusalem and the Temple of the Lord ... taking it upon themselves to sit in

the same way in which they stand for the prayer [toward Jerusalem]. They bow

down to the ground and prostrate when bowing in the qadish and qedushah,

and some or most of them prostrate to the ground whenever they are overcome

with humility and great concentration. So, too, they prostrate instead of

bowing from the waist at the beginning and end of the “forefathers” and

“thanksgiving” blessings [of the standing prayer]. They similarly prostrate at

certain moments in the “hymns of praise,” the blessings of the recitation of shema‘,

and the blessings of the [standing] prayer. In sum, they view their bowings

and prostrations as a sign of [heightened] concentration.”

Rabenu Abraham Ben HaRambam trans. Elisha Russ-Fishbane

in: Judaism, Sufism, and the Pietists of Medieval Egypt,Oxford University Press, 2015, page135 (emphases are added here)

It is clearly indicated above that the Pietists made use of these postures during liturgical recitation, but it is not often known that there was (and is) a form of prostration that was used by the Jewish Sufis in private devotions specifically as an aid to contemplative meditation.

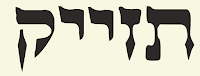

This form of prostration [תזייק tazyiq/tazzayuq] has been called “The Elijah Posture” and the “Prophetic Posture”.... the former because we have a clear reference to it having been used by Eliyahu HaNabi (I Kings 18:42) and the latter because it has been used (significantly by all three Abrahamic religions) as a posture to increase one’s receptivity to inspiration.

This

posture (ראש בין הברכיים rosh bein ha-birkhayim) is clearly something quite separate

from the prostrations that are part of the

formal recited liturgy. It is a prophetic

meditational device geared specifically to prepare and encourage the

practitioner to become receptive to a

degree of ruaḥ

ha-qodesh. This is clearly its function in the

following description by Rav Hai Gaon (939 – 1048):

[For] one who is worthy...when he seeks

to gaze at the [Divine] Chariot and the palaces of the supernal angels,there

are methods to follow: He should fast for

a certain number of days and place his head between his knees, and

softly chant many specific songs and praises towards the earth. Thereby he will gaze within — like one

who sees seven palaces with his very eyes, as if he is entering from palace to

palace seeing what is inside each one.

(translated

and quoted in Daniel C.Matt, Becoming

Elijah,page 175)

This passage

is especially significant for Jewish-Sufis as it clearly indicates the related

Sufi-adopted practice of extended fasting and (even more remarkably) the practice of zhikr

(referred to as “specific songs and praises”).

Insights into the use of the rosh

bein ha-birkhayim posture as a contemplative practice abound in the writings of

the later kabbalists. For example, in

Eben ha-Shoham(1538) R. Yosef Ibn Sayaḥ advises the

practitioner :

“To isolate himself and meditate in solitude on

matters known to us in this wisdom, and to bend his head like a reed between

his knees until all his senses are numb. Then he shall see the supernal lights

manifestly, and not just suggestively.”

(quoted in Moshe Hallamish, An Introduction to the Kabbalah, page 78)

How do we know that it was viewed this way by the Egyptian Pietists?

We know for certain that prostration was used

in this way from a manuscript fragment authored by one of Rabbenu Abraham ben

HaRambam’s own group—a manuscript that

bears a close resemblance to the style

of his father-inlaw, R.Hananel ben

Shmuel, and may even have been written by him.

Professor Paul B.

Fenton translates it for us is as

follows:

“ And Elijah went to the top of Carmel, and he bowed himself down upon the earth and put his face between his knees.(I Kings 18:42).

Elijah seated himself and put his face between his knees, intending thereby to turn away his attention and devote his meditation solely to this present pursuit. The nations [i.e., Sufis] have taken this practice over from us and have adopted and adorned themselves with it [i.e., claim they originated this practice],whereby they sit in this position for a whole day. They call it tazayyug, i.e., the concealing of one’s face in the collar, i.e., the hem of one’s garment.”

Paul B. Fenton (trans)

from A JUDEO-ARABIC COMMENTARY ON THE HAFTAROT BY HANANEL BEN SEMUEL(?),ABRAHAM MAIMONIDES’ FATHER-IN-LAW, in Maimonidean Studies,ed., A.Hyman,Vol 1,Yeshiva University Press,New York,1990,p49

The concealment of the face is familiar to us from the posture of Moses (at the burning bush and in the Cleft of the Rock) and of Elijah (at the threshold of the cave). It is also practiced by many during the first line of the Shema.

Most significantly, the faint memory of both the posture of prostration and the concealment of the face are preserved in the act of nefilat hapayim (falling on the face) during the Tahanun prayer which sometimes follows the Amidah.

Though the recitation of this prayer has become associated with self-examination and with petitionary prayer, it may well have originated in a practice of silent meditation following formal congregational prayer— the period of reflection after tefilla spoken of in Berachot 32b:24. As such, it presents us with an opportunity to open our minds and hearts to the possibility of receptive inspiration and provides us with a moment of khalwat dar anjuman in congregational worship.

But Tazayug/the Elijah Posture is quite distinct from the bowings, kneeling, and prostrations that Rabbenu Abraham promoted for congregational and private liturgy.

In our group's private devotions and vigils, in our personal zhikr and khalwa, Tazayug: The Posture of Elijah has a most special role to play in our contemplative practice as Jewish-Sufis.

©Nachman Davies

(from The Mitkarevim:Jewish Contemplatives and the

Return of Prophecy)